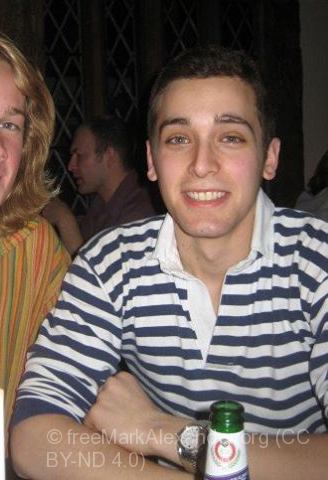

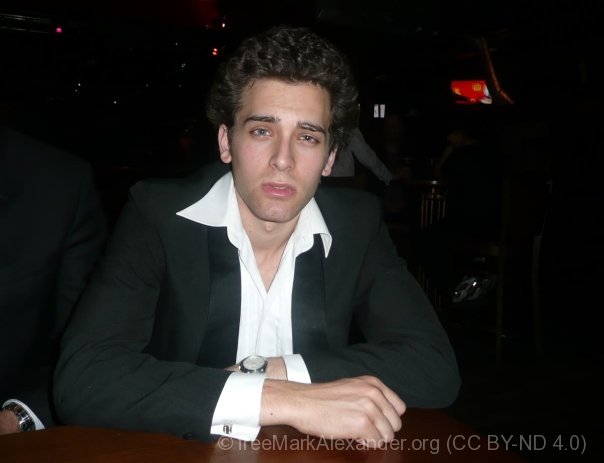

Mark’s moving and deeply personal account of his first year in prison, taken from his 2010 – 2011 diary.

“It’s hard to know where to start when I reflect on my experience of prison and this tragedy. There are so many conflicting ideas and emotions associated with this place; I think it reflects the ongoing turmoil and unsettling nature of an institution with so many complex facets. It’s been a long journey, through the worst year of my life. Usually I’d try to look for a little perspective, to step back and take in the ‘bigger picture’ whenever I felt things were getting me down. It was easy before, but I can’t really do that now, because there is no bigger picture. Everything that I loved and knew has been torn from my reach, and I find myself asking why? How could this happen?

I want to share with you what I have shared with many of my friends. After all, how can we know a man, less still be his judge, if we do not know something of his principles, his passions, his philosophy and driving force? I hope these pages will go some way toward raising awareness of my plight and the reality of this case. It is impossible to relate everything; this dossier is meant to give but an insight into my life, and thousands of pages of statements and reports. I hope you find all the answers here, but I am not a closed book. People sometimes worry about what is ‘okay’ to talk about with me, please feel comfortable enough to let all that go and ask me anything you feel like, there is nothing you can’t say.”

Part I – Imprisonment

Losing your freedom

1) You can never truly appreciate freedom until it is taken from you and the full significance of what you have lost hits you. This just can’t be simulated. We are not born into bondage, we take it for granted. I know I did. The moment I saw the bars of prison, its high walls and barbed wire – it suddenly sank in and shook me, this was real. I had spent the past fortnight in a haze of fear and distress. Nothing was clear, I was a nervous wreck. This was like jumping into an ice pool. As I walked into my cell and the iron door slammed behind me, I felt it. I wouldn’t be sleeping in a familiar, comforting bed that night. All the warmth in my life had gone. There would be no friendly faces, or reassuring embraces. Suddenly, somehow, I was being classed as inferior.

The nights alone are the hardest: the distance and detachment from my partner; the cherished sensations, sights, tastes and smells of freedom – all painfully missed, their lack of presence echoing mournfully in the silence. Something as simple as walking through a park, surrounded by lush greens and bright light; or walking down a street with a thousand choices and delights before you as you watch people stroll by –became an untouchable luxury. This was cold and lifeless – this was prison.

Imprisonment has changed my priorities and realigned my perspective. It has made me truly appreciate the blessings I had, the people I knew, and the smallest elements of the life I led. These are what make that ‘bigger picture’ as free men, and that picture overflows. There is so much in it, that we lose sight of the beautiful details. Perhaps indeed, one becomes richer through loss. I realised what all the fuss was about, why people had fought so hard for their liberty over the centuries – this was it.

Freedom is the uninhibited expression of self, the fulfilment of free will. In prison, all that is lost. The sensory palette is numbed and starved. What is life without the freedom to express that life, to taste it and immerse yourself in it? I may have my youth, the energy to create perhaps, to entertain, to express my desires, but for whom and to what end? There is no real outlet or purpose.

Life is there to be shared, to experience moments with others. It is there to build and embrace bonds with people. How can one survive in isolation? All potential is wasted. To do is to share. All alone, it loses its appeal. While I count the few blessings I have left, I feel a sense of utter futility during this hiatus of my life. On a day to day basis, life as I knew it has been taken out of my reach and become pointless. There is a sense of the mundane in every step and breath that I take which demoralises and demotivates.

Prison is a place of misery and despair. Everything is reduced to the superficial. Even my music can never be as enjoyable as it used to be. Everything I do is underlined by a deep sadness within me, and tainted by frustration at a prolonged injustice. There is a void where my father once was which only memories can fill now. I feel a constant dull pain, physically aching like a migraine.

Support from friends

2) My friends have been my family. They have brought me through the lowest, darkest depths, as I was gasping for air, when I felt like I was drowning. I have felt the warmth of generosity and support, and been touched. It means a lot to me. Hardship has made me incredibly sensitive to even the smallest acts of kindness – my heart fills and I feel lifted. These people in my life have been my greatest gift and count for more than anything. Every letter is like a ray of light into an otherwise dark prison. It breaks up this mundane existence and helps curb the sense of abandonment I often feel here, cast away and rejected by the society I cherished. The fear of being alone, of losing my hold on the world, strikes my very core – but my friends remind me I am not forgotten, that I am still loved and still believed in. I’ve heard from people I’ve not spoken to or seen for years as well, those whose paths crossed my own for even the briefest of moments. This precious contact keeps me in touch with reality, helps keep warm memories alive, and reminds me of what I have to look forward to.

There are times when I feel at a loss. I cannot be there with them or for them. I can never thank them properly of show my appreciation fully, and in the meantime, here I am. Their lives go on, the world rushes by. All those lost moments: I remain powerless. It is a bizarre sensation seeing things from the borderline when I used to be in the thick of the action.

I’ve spent over a year in prison now, it’s a sobering thought, and I am terrified. I know this will end and that things will be resolved, I believe it and feel it, but the fear is just when will that happen? How much longer will this last? When will this nightmare stop? Within our own lifetime over 137 individuals facing the prospect of life imprisonment have been wrongfully convicted in the United Kingdom, persecuted and judged without reason. They all campaigned for their innocence, all fought to clear their names, just like me. What is frightening is just how long innocent people can spend behind bars before convictions are quashed and they are exonerated. In these cases, anything from a year all the way up to 27 years. This is the reality I face. These are incredible testimonies. I can’t imagine spending these lengths of time like this, imprisoned – a life squandered. This single year has already felt like a lifetime. The uncertainty is unbearable. What lies before me? The best years of my life, the years I should be establishing my career and building a new, happy family – symbols of that miraculous renewal of life – to start something new, something special, paving the way to a better future.

Prisoners and life inside

3.1) There are those for whom it is all too much. Suicide in prison is a stark reality. I remember the shock I felt as I peered out of the flap of my cell door in my first few months here and saw the lifeless body of a young man being stretchered out of the cell opposite me. There was a reverent silence, a horrible feeling of just what he must have felt in those final moments that pushed him to take his own life. It is so drastic, so final, so cold. That was it, a future lost, a life destroyed. Only a few hours before he had been playing at the pool table. Who was to know his smile hid a bitter truth? Was this rehabilitation?

Staff lingered sheepishly at his door. Prison was only meant to teach him a lesson, this wasn’t the plan, this wasn’t supposed to happen – but it had pushed him over the edge we all walk along, teetering as if on a tight rope. It emphasised to me the fragility of life, but also its sanctity. How had this man lost sight of its gifts? There is always hope, always something to fight for. Yet, I realised with a chill that maybe that candle of hope had burnt out in him. For if hope dies, so does the soul.

The system makes broken men who succumb to the fate that has befallen them, impassively. I do not allow myself to lie in such a stupor. I have lifted myself up and strengthened my resolve. I know my father would have wanted me to. I believe in what I am fighting for, a just cause – innocence.

3.2) For many of the prisoners here though, prison is ‘easy’. They have been in and out of it most of their lives, institutionalised and fearless. It makes my sense of personal isolation here all the greater. I cannot fully relate to their lives, they come from a different world. I feel alone, a stranger – thrust into an alien environment amongst people I would never have otherwise interacted with. It is an eye opener. At times though, it is overbearing. I try to get away from this place as much as I can through reading, writing, art or music. It’s the only way really to avoid deep depression. I can’t integrate or acclimatise to it. I don’t belong.

The intrepid struggle to survive, to cope with the daily stresses and emotional turmoil which prison brings to the fore is a real challenge. You don’t serve a sentence, you survive it – this is no joke. The number one priority has to be making it through week by week, avoiding the latent danger, violence and brutality that can spring at any corner. It’s a frightening existence.

I’ve had it all here – attacked, harassed, stolen from and threatened. You have to be vigilant and alert at all times, prepared to expect the unexpected. It happens to everyone. Street culture permeates everything. It has been quite a culture shock, and while I refuse to become part of it, I have to respect it to get by.

Beyond the silence of your cell are the distant screams and shouts that echo across the prison. There’s no polite conversation over tea here. Fights break out regularly on some wings. There is little place for social or cultural pursuits – the very nature of imprisonment negates it. It is often hard to think amongst all the noise, let alone find a sense of clarity or purpose.

I often look around me and reflect on things. How on earth did I end up here? Sometimes I look around me in despair at the filth, degradation, brutality and superficiality that fills the air. At other times, I look around me in pity and well up with compassion. I encounter stories of tragedy at every turn; at the heart of it are very real and human emotions, real families, and real people. What has gone wrong?

I come across so many people here who are illiterate, they have got through life unable to read or write. It was a real shock for me. I didn’t think it happened anymore. I recently became a Mentor under a scheme run by the Shannon Trust called ‘Toe by Toe’, which teaches people how to read and write in easy steps. It is one of the best programmes run in prison because it legitimately turns lives around and instills newfound confidence in these individuals. They come to me to help them write letters and poems that connect them to loved ones and allow them to break free of their chains and express themselves. Seeing the smiles on their faces as I help them pronounce a word, or teach them new ones, is great. Nobody has really taken an interest in them before. People come to me for help and advice with their problems, or to draw portraits of their families and loved ones. I try to help out as best as I can and support and guide those who need it most.

70% of offenders return to prison within 2 years of their release. It is a shocking retention rate. I have seen scores of familiar faces return having squandered their newfound freedom. It is incredibly frustrating for me as I sit here fighting for my liberty, so precious to me, to see this kind of thing going on. There are only a few ‘courses’ here that really seem to do the job. Anything that gets prisoners to find that self-awareness and understanding of relationships and the psyche, so crucial to their existence, is a good thing. This is what is needed. We must teach them to appraise themselves, to learn to get in touch with a new depth of emotion, empathy and reasoning that can charter their lives with a positive force

For me, the course which has genuinely affected the most people and brought them to some level of enlightenment is the ‘Alpha Course’. It is an exploration of the Christian message, where people can discuss morality, ethics and theology – at its most basic and fundamental levels – in small groups with a leader. Christianity is an ideal model because of its core message and principles. It encourages belief in the self and awareness of the other. The change that I see in people through these sessions is remarkable.

I spend at least 15 hours confined to my cell each day, on weekends this can be up to 21 hours. [In 2010 – 2011] I dedicate two hours each morning to music, practicing piano or producing music in the recording studio. It is a precious outlet for creativity and the soul – a purifying ritual each day that restores a little humanity, dignity, and freedom of expression. I am currently working towards my Grade 8 piano exam with the Royal Schools of Music who are able send in an examiner when I am ready. I’m also preparing a half hour vocal recital for my Diploma in Music Performance with ABRSM, which I’m quite excited about. I’ll start working on my Grade 8 violin pieces later this year too.

I spend a lot of time reading, be it literature or self education – I’m trying to keep my French up to speed, and am teaching myself Russian. Every moment I have to spend in prison is a waste, so I try to use that time constructively to help balance the loss. I want to walk out having achieved something and bettered myself as best as I can in the circumstances.

Coping day to day

4) I’ve had to rebuild myself completely. I crumbled after the arrest, and then my trial destroyed anything that was left. It has been a slow and difficult process but I know I can’t allow myself to wallow in self-pity or depression. It won’t achieve anything. I have to be focused and proactive. I draw on the inner strength that has got me through life and spurred me on, to persevere. I’ve always tried to make the best of a bad situation. Justice will prevail, I believe that – but while this idealism is all well and good, I know that nothing can be taken for granted. I only have to look at where I am now to realise that. It’s an uphill struggle, at times it seems against all odds. Yet, I am not jaded by my experience; I still have faith in our justice system because ultimately, it is the same system that will eventually set me free and through which I may prove my innocence.

I miss having peace of mind, that feeling of kicking back and indulging oneself, of being able to relax. My mind has been wrecked with anxiety, stress and unease for a year now. I can’t remember what that peace feels like. I can never just let go or purge my mind. I just wish I could take a day off now and then, to release – but I don’t get time out. It is a relentless, unceasing ordeal and I am exhausted.

Yet, I know I can’t allow myself to be beaten down. I have to be strong for my family too. I can’t do that if I don’t have a hold on things myself. In many ways, this is harder on them than me, and I worry about them constantly. I know I could never have made it mentally in these first few years without the support of my loved ones. They kept me going and kept the fire inside me alive.

Bereavement and mourning

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraph 3]

5) There is so much uncertainty surrounding my case, we know so little, but one truth cannot be escaped: my father – the man who inspired me, moved me, and spurred me on at every step – is dead. Lost opportunities and stolen moments lie unfulfilled. Often, as I close my eyes and fall asleep, I somehow expect to awake from this nightmare, but every morning the realisation and disappointment that he is not coming back breaks my heart and fills my body with a sinking chill. A year on, I still struggle to comprehend this new reality.

My life has been turned upside down – as if struggling with the loss of my father wouldn’t be hard enough, it has been compounded by a total loss of freedom. Worse, my father has now lain in rest for over a year, and I still haven’t been given the chance to visit his graveside. We know nothing of the spiritual world or the existence of an afterlife, but Christianity is founded on such beliefs and reassurances. The bond between a father and son shouldn’t be broken like this. The funeral, memorial, tomb and grave are all incredibly symbolic, and graveyards exist for a reason. They serve as a permanent, physical reminder of those we have lost, providing a focal point for reflection and remembrance. I am reminded of my father’s death every single day that I remain here, because it lies at the very epicentre of why I have been locked away like this, why I was accused of murder, and why I now fight to clear my name. While I remain here, any sense of closure or coming to terms with my father’s death is simply an impossibility and remains incomplete. There is no alternative focal point. There is no source of solace or renewal.

I wasn’t allowed to go to my father’s funeral while I was remanded in custody. It left me all the more devastated. The mourning process is a complex thing, each person going through a unique journey. Being denied such an important step as this in bereavement is a travesty. His life ended far too soon and without explanation. Just as he was stolen from me, this opportunity was stolen too. One of the things that helped me through the first phases of grief was preparing the memorial service in his honour. I wanted to give him a worthy send off and the peace he so greatly deserved. I carefully chose the hymns and readings, with a choir and organist, and I wrote a eulogy dedicated to his life, expressing the unsaid words and feelings that I wish I still had the chance to say to him.

Everything was set for Tuesday 27 April 2010, shortly after what should have been his 71st birthday. Prayers were held at St George’s Orthodox Cathedral that morning in accordance with our heritage, with Bishops and priests drawn in from three parishes who gave generously of their time and support. They worked closely with me in the build up to the ceremonies. The Anglican memorial service followed at Holy Trinity Church in Drayton Parslow, our home for the past 22 years, and where my father was finally laid to rest.

I was all he had – his only child, his confidant, his friend. Having spent my life with him and nursed him through illness I had grown to understand him and love him like no other. The service went ahead without a single relation of the family there for him. It stripped much of the poignancy and dignity from what should have been a monumental moment. He deserved better than this. By taking this away from me, I was being treated like a criminal long before my trial had even taken place. My lack of presence at dad’s funeral said more for the prosecution’s allegations than any words could. It helped forge a psychological bias in their favour.

A view inside a prison cell

6) You can spend the day trying to distract yourself, but the harsh reality rushes back every evening. The iron door, pock marked with dents where past occupants have kicked their frustration out on it, seems to fill the room. There is no getting away from prison at night, the sounds of jangling keys and beeping radios drift through the air and my broken sleep. Every few hours the flap opens and a strange eye looks through, there is no such thing as privacy. The beds are wrought iron, this is no hotel experience. Standard issue mattresses and bedding are there by necessity, not for comfort. The walls are usually covered in graffiti when you arrive, and traces of the posters that have been stuck on them over the years with toothpaste or boiled down coffee sweetener for glue remain scattered across them. Barred windows look out over littered courtyards: covered in unwanted food, banana skins, empty cans and packaging, toilet roll and shattered glass. It’s a waste ground that rots and stinks, attracting pigeons in their flocks to scavenge amongst the seething filth. If you’re lucky, you’ll get a view across the green grass and the occasional trees that run up to the high fences, crowned in barbed wire, and the last concrete wall – a grey horizon, the vestige of a prison that rings off a world beyond our reach.

The sound of dozens of cell doors being kicked ritualistically in the middle of the night becomes familiar, as prisoners celebrate the results of football matches, or gloat over appearances on the news. Having a cell to yourself is a real privilege, it makes a huge difference. Such privacy comes at a premium here.

There are moments when beauty manages to reach even the harshest, most desolate of places. Nature pours its pure bounty over the decadence of mankind’s construction and destruction: the colours of a sunrise that crown the horizon; the fog that envelopes the walls of prison in a soft blanket; the drops of dew that form on the high grated fences and glisten like diamonds in the sunlight; the fresh snow that softens the malevolence of the barbed wire; the footprints of a frolicking partridge as it bounces across the wastelands; the soft chatter of baby ducklings lilting across the walkways as they meander in line behind their mothers. They are comforting sights. Yet I remain a spectator, and the world beyond these walls goes on. Often I can hear the rush of passing traffic, or the low hum of planes high above us, people just going about their lives – and it feels strange how a world of freedom can be so close and yet so far.

Now and then, familiar sounds and sensations spark recollections of the past or those reassuring noises that fill our homes, and I am caught by surprise and delight for a fleeting moment as if bumping into an old friend on the street. I am often filled with deep nostalgia. As my birthday, Christmas, and New Year went by I fell back on sweeter memories of the years before spent with friends and loved ones – wondering what they would be doing this year, wishing I was there, imagining what we could all be doing, and looking forward to the next time we would be together again. They are both cosy thoughts and choking ones. The reality of what is, compared with what should be. The weight of all these lost moments and experiences over this year is overwhelming. I long to share and feel again, and often this longing fills me with tears of desolation.

Part II – Accusation

Police arrest

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraphs 74, 75, 76]

7) The first arrest was simply surreal. I’d spent over two hours chatting with the police officers as we sat around my flat and tried to make sense of where my father could be. The ‘caution’ was sprung on me so suddenly after all this that it knocked the wind out of me. They thought something had happened to my father. That was really too much for me to take or digest, and I broke into tears.

When we opened the door to the police that night, it was as if we had welcomed in some far fetched alternate reality that would cripple our lives, as unexpected as it was unbelievable. It’s the kind of stuff you hear of and listen to in horror and disbelief, thankful it is only a story. In the fortnight that followed, I was told not only that the father I had thought was alive was actually dead, but that the mother I had spent my life believing was dead was actually alive. I had lost and gained in one fatal stroke. I found myself consumed not only with grief, but by a plague of accusation in which I was being held responsible for the very loss I was struggling to come to terms with. Each hour that followed went past in a dull haze. Pure shock filled my body, a chill that made me break into spells of physical shivering. Nothing can prepare you for something like this.

I remember thinking – as the two officers led me downstairs and out onto Fleet Street – that I’d be back soon enough and we’d be laughing this off the next day, relating the fright of our lives to our friends. I expected dad to rush to my aid any moment, that this was just a formality until he showed up, outraged, and viciously berating the police for being so heavy handed. I look back, shamefully now, at how I even felt slightly annoyed that dad had let this happen in the first place. I still hadn’t realised my own negligence. It’s so strange recalling that moment: stepping onto Fleet Street in handcuffs that evening, flanked by officers, and looking up at the dim light that shone over our balcony, our home – oblivious to my fate, and being led away from it all. It just didn’t click with me that I was a ‘suspect’ for something.

When I was released on bail a few days later – delivered amicably to London by the very same officers who had been relentlessly interrogating me – I left the police escort that night a shadow of my former self, numbed to the warmth and comfort that welcomed me back. I was so happy to see my partner again and recover in a homely place with friendly faces around me as we tried to piece together a way of finding dad. It turned out we couldn’t return to our flat. When we were eventually let back in, the place was littered with empty MacDonald’s boxes, Starbucks paper cups and even a pizza box; it looked like the remnants of a lad’s night in. Our flat had been used as the police cafeteria. While my partner and I had been tormented out of our wits they’d been kicking back on our sofa and enjoying our TV. In the meantime, the police had more or less taken everything else. My partner’s laptops with all her university notes, our phones, our iPods, her camera, even our all-in-one printer had been seized. It made any return to normality impossible and completely debilitated her for the next 6 months.

Everyone looked after me as best as they could, but it was short lived. I was soon bundled into a black BMW by three large men and raced back to the police station. A female officer had called my partner on her mobile saying she was outside our apartment and had some of her property to return. Instead, as we let them in, they crowded into our tiny flat, seized her phone, and explained they were actually taking me away. I wasn’t sure what to think as they rearrested me, their words didn’t sink in, but I remember telling my partner “everything will be alright” as they placed me into handcuffs. I remember shivering through the 40 minute drive to the police station, stunned and silent, bracing myself. Why all this drama? There must be another misunderstanding I thought, but the next time my partner and I saw each other again was in a prison visiting hall.

Revelations: being told my father had died

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraphs 75, 76]

8) I never believed things would go this far. I couldn’t accept my father had come to any harm. In the shock of my arrest, I desperately tried to look for reassurance, trying to convince myself everything was alright, that this would all end as quickly as it had begun. On bail, I set about trying to find my father. Had he got himself into trouble? Was he running from something? I chased missing person’s agencies and made frantic calls. I had poured out hours of interviews, without a solicitor, in my eagerness to help the police find him. I didn’t think of myself or realise how confused I really was in all this. It was in total disregard of what my legal training had taught me, yet I thought nothing of it. This was my dad: the resourceful, independent, spontaneous man I idolised and adored. The last thing you think of is your own parent’s death. You cling to hope and look at every other possibility except that.

As things progressed I felt powerless and helpless. I found myself being the last to know everything. I remember crying in the arms of a friend as she told me how the newspapers were revealing my mother had been found. It all seemed so impossible. I scoured the internet for clues and the latest developments. I found out my father was dead from the news, not the police, but the BBC. I remember the disbelief, the angry tears, the hollowness, as I sat in that prison cell isolated and traumatised, watching the report unfold: seeing my father’s face fading on the screen; switching it off in horror; literally pinching myself as I seemed to go numb; and lying back on the iron bunk bed refusing to believe what I had just heard.

‘They must have made a mistake, it must be someone else’. I remember seeing the cordons surrounding our home, wondering when I could go back, when all this would be over, what all these strangers were doing there. This was my home on the screen, distant and impersonal – I felt violated.

A once vibrant home now lies unloved and forgotten, overgrown and dusty; a stark relic of a tragedy; the object of speculation and neighbourhood scandal, the hypocritical shaking of heads and hushed gossip. It is as humiliating as it is frustrating.

Solitary confinement in Police detention

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraph 76]

9) The police cell I spent nearly a week in after my arrest drove me to distraction and total collapse. It was a void in space and time. I was stripped of shoes, belt, and watch – fermenting in the few clothes I was arrested in, without any grasp of time or sense of humanity. I strained to count the hours that crept by, a shaft of light from a few opaque blocks of glass on high my only indicator of the passing day. There was a slab for a bed in one corner and a toilet in the other, overlooked by a camera and microphone. The silence was quite literally ‘deafening’. I didn’t understand this expression before, but now it made perfect sense. That complete and endless lack of human presence or sound was so overwhelming that it became unbearable. I sang to myself to try and keep my wits, shivering in a corner, huddled in a ball. All I could hear was the low hum of an extractor fan, and the buzz of the electric light – constant and relentless. There was no indication of how long this would last. In the end I spent over 100 hours like this. There was a sink I had to push a button to get a short stream of water from. You could only press it a few times before it cut out completely. 3 times a day the hatch would open and a small microwaved meal would pop through.

I was shuffled in and out of this cell to an interrogation suite, exhausted, starved and traumatised. I spent 12 hours in the suite overall, often called in around midnight. Everyone naturally reacts in different ways and in varying degrees to trauma. For me, I was devastated both mentally and physically – a wreck. The state of confusion I was in threw everything into disarray and the mistakes I naturally made in my interview were picked upon by the prosecution at my trial. I worried about my loved ones constantly. I had one short call a day. Frantic and distressed as I was, it was a momentary window to reality.

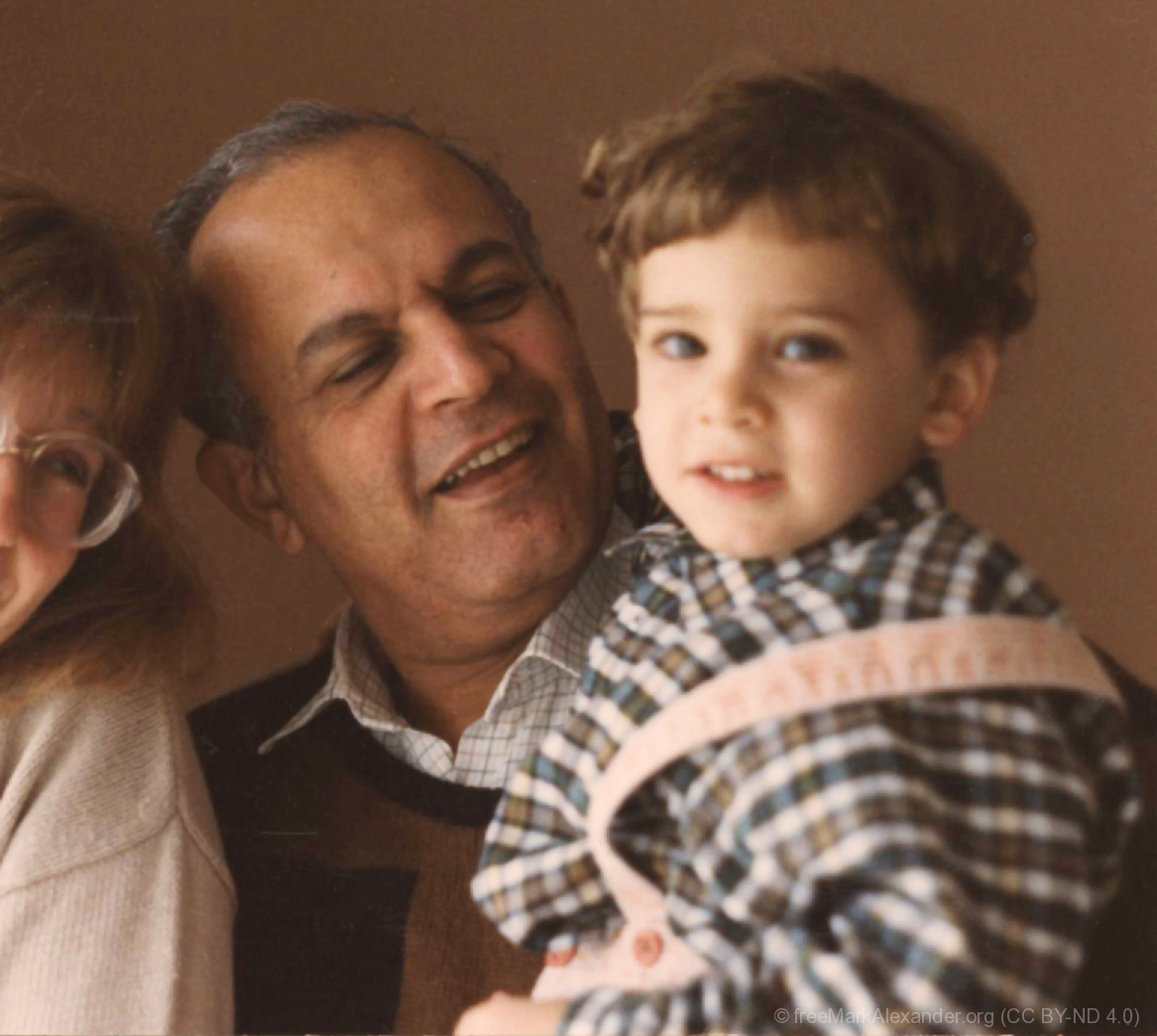

Searching my father's hidden past

10.1) I was always aware of my father’s devotion and love. Everything he ever did was done with the best intentions. Whether it was protective, or supportive, the purpose was always pure. Yet, he always maintained a distance between us. It was a relationship of parameters. It would be too simplistic to say we weren’t close as father and son because we loved each other deeply, but there were barriers I couldn’t cross and questions that couldn’t be asked. As I discover more about his life, I realise that I never really knew what lay behind the mask he wore all those years. I understood his character, his likes, dislikes and temperaments, but that was where it all stopped. His was a book that did not want to be read. In many ways, I think he maintained this to protect me from the truth, to bring me up to be something different, someone different. The question today is: what is that truth? I am not only discovering more about my own father, but more about myself in the process.

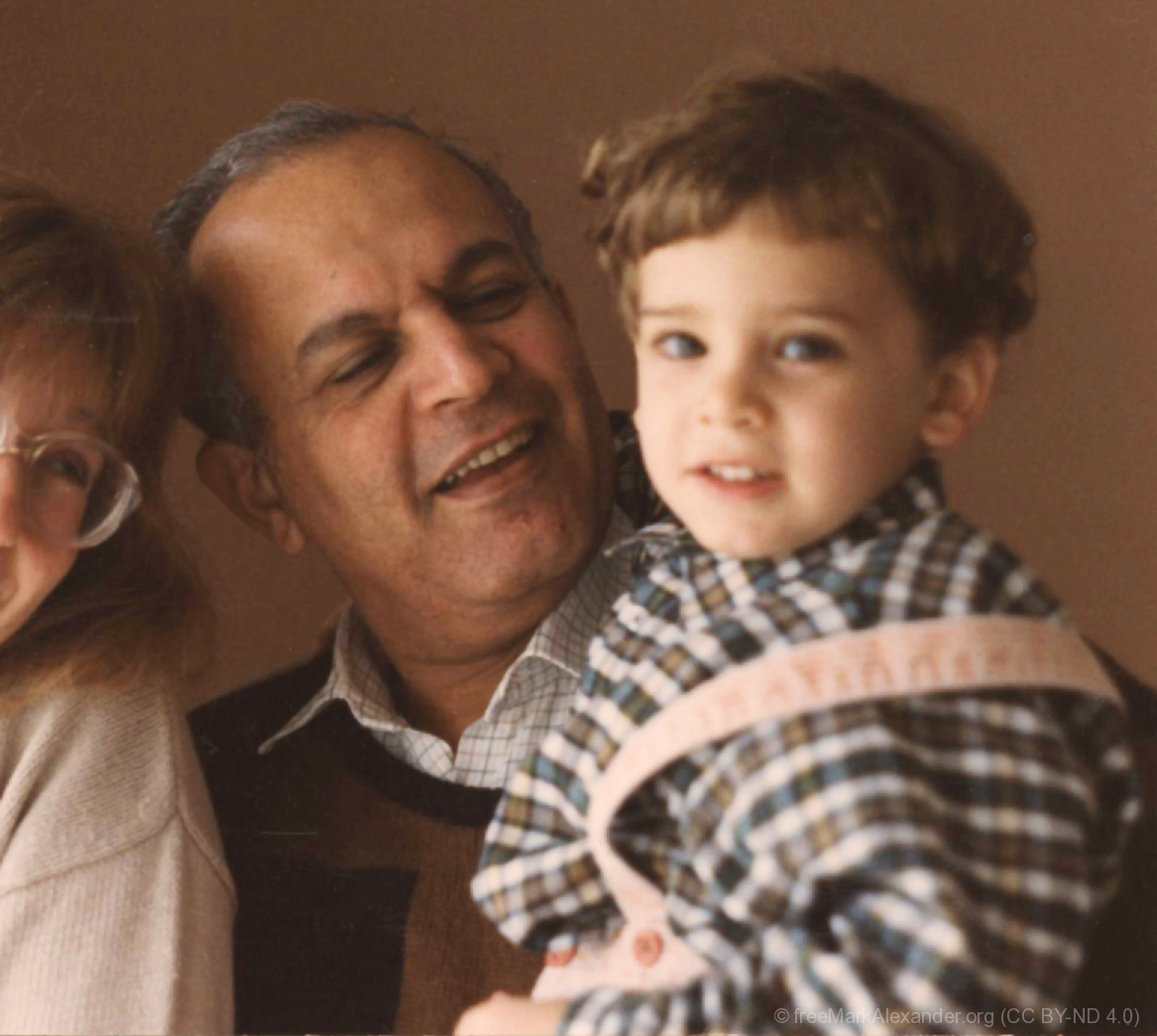

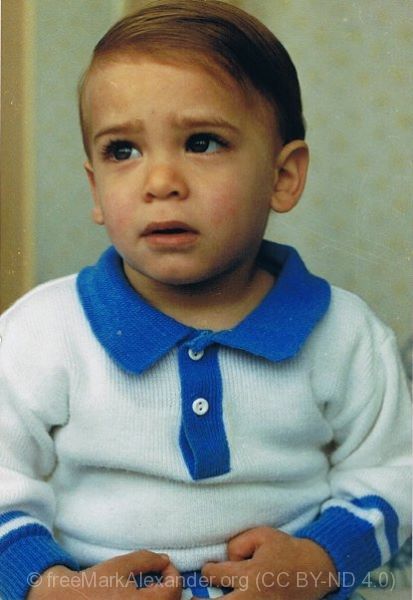

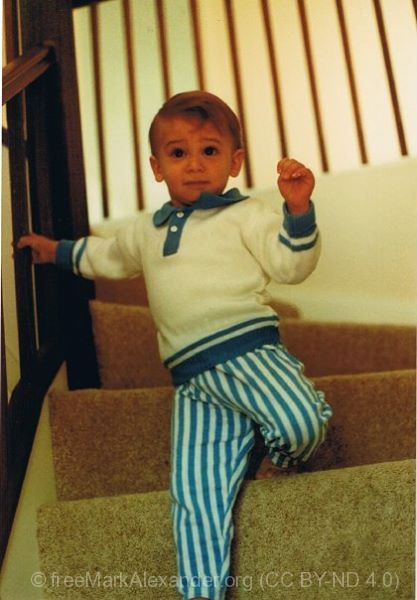

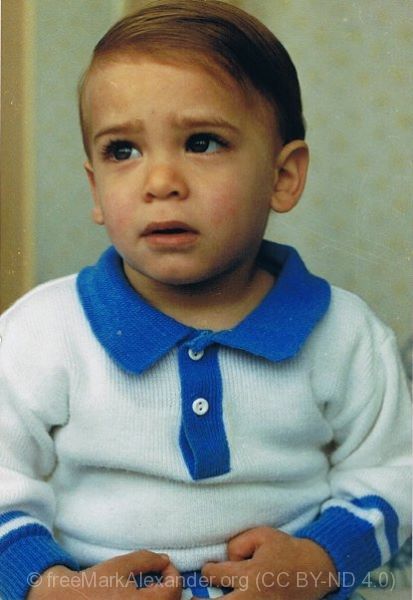

10.2) Dad was born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1939, christened Sami Fahmi Yacoub El-Kalyoubi. Whilst in Cairo, he was chosen by his government amongst top national graduates for scholarship to foreign universities. Turning down an offer from IBM, he was sent to Ireland. After graduating in English Literature from Trinity College Dublin he initially returned to Egypt before eventually settling in London in 1968. I know little about these early years in England other than that he married briefly, moonlighted in practically every profession, and made his fortune. Almost 20 years later he took early retirement when I was born. He had met my mother when she was just 18 years old and devoted himself to raising me. It was by this point that he seems to have started running away from things, creating new identities, cutting himself off from people, and struggling with spiralling debts.

I remember trying to find a sense of reason after my arrest. Where was my dad? The only thing that made sense to me was that he was on the run. Had his past caught up with him? ‘He’s taken it too far’ I thought, ‘this time he’s got himself into real trouble’. In my speculation I tried everything, even calling on friends with links in the intelligence community hoping there was something they could tell me. I wanted to protect him. I was incredibly shaken by it all and the time I’d spent in isolation had hit me hard. My paranoia built, and I walked around London with a sense of fear, looking over my shoulder at every turn. If something had happened, would I be targeted? Was it safe for us? I had to look after my partner.

At my trial I explained that I had told some lies in my interview with the police because I was trying to protect my father from the little that I did know about him. I’m not proud of this, but at the time I didn’t want to get him in any more trouble. The focus was finding him – this was a missing person’s enquiry. Had he turned up alive and well as I expected, none of this would have counted against me at my trial.

There can only be two possible reasons and motives for my father to be murdered – if he was – and one of them is monetary. Did he owe people money? Why else develop such elaborate aliases? Each had a fake address, nationality, date of birth, academic history. It was enough to register himself with a different GP in each county and buy property. Why was none of this investigated?

I know all this because I saw him doing it when I was younger. I had to live these identities as a child. Between the ages of 6 and 16 I took on a new identity almost every year, constantly changing schools, learning to be someone else, having to remember my new name and new life. Of course, I didn’t know any better.

I know all this because I saw him doing it when I was younger. I had to live these identities as a child. Between the ages of 6 and 16 I took on a new identity almost every year, constantly changing schools, learning to be someone else, having to remember my new name and new life. Of course, I didn’t know any better.

Knowing as I do now that he defrauded companies, and as my mother revealed, that he left her penniless too, tricking her into signing away all she had – one of my fears is that he may have tried this on with the ‘wrong’ people, or got involved in something, and it all went horribly wrong.

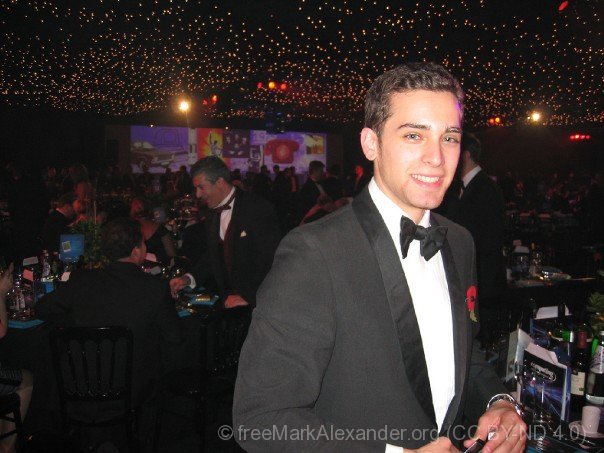

Hearing the trial verdict

11) As the trial approached, I was sure the nightmare would soon end. I never prepared myself for the worst. I simply didn’t allow for it. I built up my hopes, shared plans and looked forward to the relief – at long last – of 6 months of trauma; to a new approach to life. I wanted to take hold of my life once more and make the most of everything, to honour my father’s memory. I felt that somehow, in all this tragedy, I had learnt something deeper about life, found some sense of reason.

We had made breakthrough after breakthrough and the support from friends and colleagues had been overwhelming. ‘They couldn’t make that kind of mistake; they couldn’t send an innocent man to waste away in prison’. I was so self-assured, but the legal system doesn’t work in the way I had perhaps naively expected. It is a complex, human machine, and sometimes things go wrong. From the ideological principles and theorems of the lecture hall to the tactical drama of the courtroom, something goes awry.

I remember that last moment of the seventh week of my trial: the jury coming in after over 12 hours of deliberation. My heart pounded like I had never felt before, my fate and very life hung on the tip of a man’s tongue, on just one word. I only heard ‘guilty’. Had I missed the ‘not’? I looked around me and saw only pity. I didn’t hear the judge speaking, I couldn’t, everything was drowned in the flood of my shock. I was supposed to be walking out now, breathing freedom, touching liberated soil. Instead, I had entered some parallel dimension, some cruel, twisted world. My legs gave way, my mouth dried up and locked itself open in aghast. Why me? How could my God let this happen?

Yet that majority verdict, 10 to 2, was all too real. I looked questioningly at the jury for answers, but they couldn’t return my gaze. Many held hands to faces, one left the court in tears. In the viewing gallery, blocked from my sight, all I could hear were protesting cries and stifled sobs. I couldn’t bear the pain my loved ones would feel. It struck me as hard as the verdict itself. Then the tears came.

Post-trial quarantine

12) Taken back to prison after the verdict, they feared the worst. They knew I hadn’t seen this coming. I was placed in a Perspex cell on their hospital ward, stripped of all my possessions, without so much as pen or paper when all I wanted to do was start preparing my protest. ‘This couldn’t be happening’, it was all so bizarre. I spent the next few days in this barren room, a guard posted at my transparent door through the day and through the night. I lay in bed curled up and shell shocked, detached from the world and ruined. Voices felt distant, the steps I took didn’t feel like my own. Everything I experienced seemed physically numbed. Through the sense of alienation and abandonment I struggled to comprehend reality, fate, and faith. Everything had suddenly been thrown into disarray and confusion. Everything I had ever believed in and every thought process questioned. I spent the next few months searching for my lost self. I had to pick myself back up again, slowly but surely – recalibrated and reconfigured.

Public perception and the Press

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraph 3]

13) Being on the other side of the fence as it were, looking out from the courtroom dock rather than looking in with the rest of the public, is an incredibly surreal experience. Not so long before, I had been sitting in on trials as a law student myself, inspired and awe struck by the majesty and tradition of the place. I couldn’t understand how I could be praised one day and then deplored the next. I was certain they would see through all that. The legal system I had dedicated my university life to promises the principle of ‘innocence until proven guilty’. Yet here I was, stripped of my freedoms and labelled a murderer by the tabloids before I’d even gone on trial. I had to admit that in practice, we often see people as guilty until proven innocent.

In the same way, as much as it may hurt, I appreciate how against the backdrop of sensationalist press, the public – as it naturally must – not only takes the published word as gospel, but formulates their own prejudices and assumptions on the inaccuracies portrayed as truth. I know, because I remember how I had shared these prejudices myself as I grew up. I realised the bitter irony that now the tables had turned. In life, we learn that we can’t possibly please everyone, so I don’t try to, indeed one doesn’t need to. Placing our legal system on a pedestal, we find it hard to reconcile ourselves with the fact that miscarriages of justice actually happen, that things can actually go wrong. Better to be a doubting Thomas until proof materialises, than speculate about a system which is capable of setting a guilty individual free and sending an innocent to prison. It goes against the grain, we don’t like to hear about it because it undermines the trust and faith we place in the police and courts. I am not blind to all this, it is what makes my journey and struggle all the harder, but at the same time it makes me all the more determined to prove my innocence. ‘The foundation of justice is good faith’ – Cicero.

Trial reflections and critique

14.1) The overriding picture, what matters most, is the loss of my father. When you are investigating a ‘murder’ this must be the focus, not conviction quotas, image, or budgets. When you are pointing your finger at another human with this kind of earth shattering accusation, you are taking on the role of creator and destructor all at once – their life is in your hands. This cannot be taken lightly. With it comes responsibility and you must be certain, “beyond all reasonable doubt”, that this person is guilty. Where is that certainty here?

How did my father die? Nobody knows. When did he die? They cannot be certain. There is no DNA, no fingerprints, no trace of blood, no sign of a struggle, no eyewitness, and no weapon. As we solve the unsolved crimes of the last century, how can this be? How can we be satisfied with this? There is no known cause of death, the Judge himself admitting “we may never know what happened to Samuel”. Yet, I stand convicted of a murder than I not only didn’t commit, but which may never have happened.

How can a jury safely infer intent – an ‘intention to kill’ being fundamental to any conviction of murder – when the circumstances of my father’s death are unknown?

In England, we may rely on ‘circumstantial evidence’ to make and swing a conviction, to make all the above disappear. And disappear it did, in a maze of information and misinformation over 7 exhausting weeks. The jury were visibly worn out.

14.2) I was an easy target for police. An only son of an elusive father, the last known person they could find to have seen him. They had a field day with my family life. I had opened myself up to them only to find it used against me. They focused on my unconventional upbringing and our own way of doing things as father and son to create an air of suspicion, playing on a mistrust of the unusual. They were looking to “build a picture” – glossing over inconsistencies, any mistakes they had made in the process, and the things that didn’t suit them – forcing odd puzzle pieces together in the hope that we wouldn’t be able to knock them back out.

Yet, no amount of pure suspicion can be enough to condemn a man. This is the realm of neighbourhood gossip and speculation, not criminal culpability. It is as if they stood me in front of a mirror and shattered the glass until the reflection finally suited their purpose. Even when you are able to say to the jury, ‘well that piece should be there and that one there’, the picture remains shattered. Assertions couldn’t be ‘unsaid’. The damaging effect of words in the opening speech and beyond still remained even when totally disproved, serving only to confuse the jury and leave a false impression. My duty solicitor had summed it all up as I sat with her in the police station: “they are hell bent on proving you are somehow responsible Mark”. Haunting words. It was simply easier for them to focus on me rather than pursue difficult yet crucial investigations into my father’s murky past and secretive activities.

In a trial like this where subjectivity overshadows objectivity, connecting with the jury is crucial, and a lot is lost in the drama of the courtroom. At times, I felt like I was watching a surreal TV adaptation, while frustrated at other times that I couldn’t just stand up and say something, make an explanation or ask a question. The bizarre reality of being a spectator at my own trial, sitting in submissive silence and watching events unfold without any sense of control creates a feeling of utter helplessness.

14.3) It was an incredibly raw experience at the trial. I opened myself up to the jury in ways I had never done before with anyone. I laid myself bare. How could they relate to my life? These were total strangers. Would they understand me, who I was, what I stood for? Without any defence witnesses they had to take my word it: that this was my life, in all its complexities, expressed as best as I could.

I was shattered throughout. It was as much an endurance test as anything else. 7 weeks of early mornings and long cramped journeys, tossed about in a bare metal cage as I tried to fight for an extra moment of rest, had taken its toll on me.

By the end of the trial it was impossible to determine what the verdict would be. I could walk out vindicated of the accusations, or in handcuffs. Nobody seemed to know for sure. I was baffled. The result cannot be a mere lottery; else it is a mockery of justice. When so much is at stake it should be clear by the end whether a man is guilty or not. Yet the system does not provide such guarantees. A different jury, on a different day could find the same man innocent.

It would be a different story if we were judged by our peers, those with tangible insight and experience. My life was in the hands of ordinary people I had never got the chance to even know, but I placed my trust and faith in them all the same, they represented the very best of our legal tradition, a testament to equality and fairness. Yet, they can only truly fulfil their role if they are able to find clarity and are not misled. Without clarity we encounter difficulties and mistakes happen, as they have here. The prosecution’s barrage of red herrings only served to distract and cloud the jury.

14.4) In the meantime, the extent of negative and unbalanced press feeding off the prosecution claims, before and during the trial, was soul destroying. I read the reports with disbelief and dread. Who were they writing about? This wasn’t me. The press aren’t at fault; they relied on the prosecution for information and did their job. It is what they were given which was intentionally misleading, and that is the problem. Sensationalist coverage with headlines like “Dad killer” scattered across the tabloids and internet couldn’t have helped even the most impartial of juries.

In retrospect, some people ask me why I didn’t just plead to ‘manslaughter’ – I would ‘only’ be serving a few years now, they tell me. The answer is simple: principle. I will never admit to something I haven’t done just for the sake of making things easier on myself, how can that be conscionable? I knew long before my trial that ‘manslaughter’ would be a ‘safe’ option if I was guilty, and if I was guilty this is what I would have done. Is this the price of innocence? That I spend 16 years imprisoned for upholding an ideal? It is a strange balance to lay on any man’s conscience, but one might say it is a worthy cost – I hope in time I am proven right.

In retrospect, some people ask me why I didn’t just plead to ‘manslaughter’ – I would ‘only’ be serving a few years now, they tell me. The answer is simple: principle. I will never admit to something I haven’t done just for the sake of making things easier on myself, how can that be conscionable? I knew long before my trial that ‘manslaughter’ would be a ‘safe’ option if I was guilty, and if I was guilty this is what I would have done. Is this the price of innocence? That I spend 16 years imprisoned for upholding an ideal? It is a strange balance to lay on any man’s conscience, but one might say it is a worthy cost – I hope in time I am proven right.

Finding my father’s death manipulated in Court

15.1) One of the hardest things to have to hear and cope with as a son is being told that your own father wasn’t just murdered, but that his body was dismembered. As the reality of his death struck me, the brutality and horror of what these people had allegedly done to my father shook me for months. I couldn’t bear the thought of what he might have suffered. How had my father got involved with anyone even capable of doing such things? It frightened me. They couldn’t get away with this.

When I found out, as experts revealed, that the police had been wrong all along – my father’s body had never been dismembered – I felt both relief and outrage. I felt like the butt of a cruel joke. How could they get something like that wrong? What other mistakes had they made?

Yet, the prosecution maintained the fallacy regardless, to generate an emotional reaction from the jury. They had played with me, now they were toying with them. The prosecution’s opening speech was manipulated to send shockwaves of horror across the courtroom right from the start, for maximum impact.

They then had an electric saw – already scientifically proven to be irrelevant to the investigation months earlier – passed around the courtroom and jury so everyone could get a good look. It was a gruesome gimmick. I had to sit back and watch in horror from my barricaded box as these bizarre charades played out. They were using my father against me before casually putting their hands up and admitting they’d made a mistake – by which point of course, the damage was done.

While I had the small consolation that at least my father hadn’t been treated in the way they’d initially suggested, seeing them play with his dignity like this sickened me. Their persistence told me more about their strategy and game plan than anything. I lost my trust in the police; I lost my faith in an impartial prosecution. They didn’t care about justice, it was all about winning. Did it matter who they convicted? I began to think they really didn’t care, as along as they got someone. Was this how they served the public interest? I had trusted them to find my dad’s killer – they hadn’t. I had trusted them to tell me how and when my father died – they hadn’t. I had put my faith in forensics to prove my innocence – and they failed.

Blunder after blunder was slowly revealed. The corners cut and avenues of enquiry left untouched in this investigation frustrate and haunt me every day. There was no trace of any crime or disturbance at our home. So where was my father when all this happened? It doesn’t add up. Why was the local area not combed for evidence, even speculatively?

15.2) The investigating officer who interviewed my girlfriend, tormented her with the words: “He is responsible, there’s no hope. None”. This was before I’d even been charged. The police were proclaiming my guilt whilst I was still being interviewed at their station. It is indicative of their conduct throughout. My duty solicitor had been right, their mindset and bias was blatantly clear. If this was the kind of thing they were saying to my own partner, what had they been saying to other witnesses? The police have an obligation to act impartially and maintain the highest standards of conduct, not to harass or intimidate people. This doesn’t just call into question the reliability of their evidence; it casts serious aspersions over their entire investigation because this attitude would have directly affected their decision making process.

The search must go on; there are too many unanswered questions. I desperately want to find the people responsible for my father’s death and burial. Somebody must know something, the idea that these people are still out there is terrifying. They can’t be living in a void. They haven’t just taken my father’s life – they have taken mine, our family’s – this touches everyone, devastates and destroys. How can they live knowing this? Every day I hope that somebody will just come forward, that this will end as suddenly as it began. Over a year has passed and I feel powerless behind these bars. There is so much I want to do, so much I want to give, so much passion and hope: all wasted, all as futile as my very existence in a caged room hidden from the world. I’m looking for answers. I’m looking for change. I hope my campaign will encourage people not just to support my cause as I seek to clear my name, but to help our family find closure by exposing the real perpetrators behind this tragedy.

Preparing your defence in prison

16) Desperate to end the ordeal, I pushed my new legal team for a deadline just 3 months away when they hadn’t even had a chance to pick up the paperwork. I underestimated just how much time we really needed to prepare our case. Things happen much more slowly when you are behind bars. We were receiving new bundles of evidence and paperwork each week, up to 23rd August, the 4th week of my trial. It was a struggle to keep up. The court had not given us more time to prepare, despite our requests, so inevitably sacrifices and judgement calls had to be made, lines of enquiry prioritised and others abandoned. Judge Zoe Smith had refused such an extension at my ‘plea and case management hearing’ on 22nd June, yet a fundamental prerequisite to a fair trial is that you are given “adequate time and facilities” to prepare your defence.

It meant for example that we couldn’t even sit down to consider calling our own defence witnesses until the prosecution had closed their case and I had come off the stand. Even if we wanted to call them, the jury didn’t have the time to hear them. They were already a week over the 6 week schedule, with holidays booked and other commitments that couldn’t be put off any longer. From the 38 character witnesses we had already collected, and family members in addition, we were forced to close our case with just one witness: our concrete expert.

As I awaited trial, I faced the daily frustration of restricted liberty and communication. Without bail I – like all those remanded in prisons awaiting trial – found preparing for my defence handicapped and hindered at every stage. What can be done in 5 minutes of liberty takes 3 to 4 weeks when imprisoned. The court had been willing to grant me bail, but at the right price, money I simply didn’t have. In essence, I was priced out of freedom. Contacting witnesses, gathering evidence and so forth was an impossible task. In this way, things are heavily weighted in favour of an unrestricted prosecution with the full backing of the police.

There is no internet here, so luxuries like email and Google are out of the question. Making phone calls is only allowed at certain times of the day, and is restricted to limited individuals registered by application to the prison. You have to work within a fixed weekly allowance of phone credit and can’t receive calls. Everyone is treated in the same way regardless of their charges or culpability. There are no exceptions. I was forced to rely on my partner and our friends to chase things up, look up information, contact people for me and do all the footwork I desperately needed done and by rights should have been doing myself. This is no different today. Without them, I would be powerless. In the meantime, the world rushes by and precious time is lost. Staying up to date is a nightmare. The effect was that I was being treated like a criminal long before I’d been to trial. ‘Equality of arms’ under such conditions is impossible.

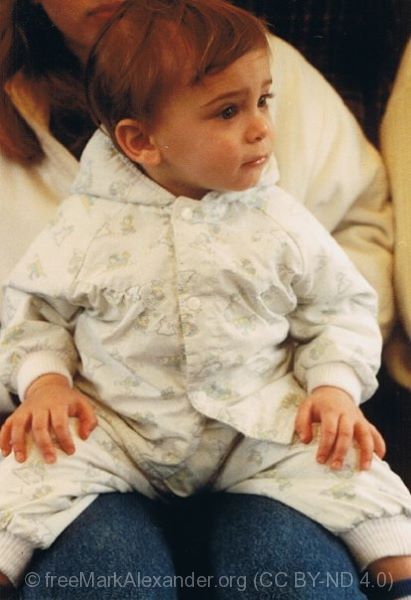

Reunited – finding my mother

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraph 43]

17.1) I was brought up believing my mother had succumbed in a battle against breast cancer, dying young. In truth, it was my father’s cover story for her disappearance. This revelation came at the same moment that my father was feared dead. The sense of my ordered world was being flipped on its head. I didn’t want to meet my mother for the first time while I was in a prison. I wanted everything to be perfect, a moment that we could look back upon in years to come. I wanted it to feel comfortable for both of us. I had banked on being given bail in the run up to my trial so I could do all those crucial things like arranging my father’s funeral, meeting my mother, consoling my girlfriend, and preparing my defence effectively. But bail never came, and in this despair I had to manage all these things as best as I could from the confines of a cell.

The day soon came when I sat nervously in the visiting hall waiting for my mother to arrive: wondering what she would look like now, what she would be wearing, what our first words would be to each other, what she would say – and not really knowing what I would feel. I had hazy images of her from my earliest years. I remembered her vibrant, bubbly nature, her gentleness and vulnerability; how she loved music and would dance around the house all the time. I remembered her warm smile, and as she walked in that day it was the first thing I saw. I felt instantly at ease.

The rest was natural, moving and touching. The desperation and injustice of our plight and the tragedy of Sami’s death brought us to tears. I listened to her stories of the past, and learnt her side of the family tale, tainted with pain and strife. I had never been allowed to see any of them; they were kept away – much like my father’s own family who I am only starting to talk to for the first time now. Making that connection in light of such stark and shocking loss and having to introduce myself against this backdrop has made an already gigantic leap even more daunting. In rediscovering my family like this I am learning more and more about my father’s past.

It is like shining a light on a strange and dark place. I step forward into the unknown with dread and fascination. I have heard so much now that nothing surprises me anymore. It was hard to listen to mum relate how dad used to mistreat her. I don’t like hearing about him in this way, we should remember those we have lost for their qualities and through our most cherished memories of them, but I also know it is crucial to understanding my father better. Disturbingly, my birth certificate bears a false name where my mother’s should be.

Having lost my father, I will never know now why he lied to me like this about my mother. Perhaps he felt it would be easier on me as a child. I often try to second-guess his inner conflicts. Maybe as I grew older it simply became too hard to reveal, too much of a shake up. Perhaps the lie simply became second nature, a comforting fallacy?

My mother spoke candidly to me about his affairs while they were together and how he used to beat her. I was sorry dad had treated her this way; I knew it wasn’t fair on her but also understood that it was a complex relationship that simply wasn’t working for them. I tried to console her while she promised to make up for all the years we had lost. She felt guilty that she had been too scared of Sami to try and get in touch with me any sooner.

We shared happier tales as well and I felt that special warmth that comes over you when thinking fondly of a loved one you remember. The familiar jokes my father would tell, his charm and sharp wit, the altruism and care he so often showed – each little anecdote a new treasure.

17.2) To top our reunion off I learnt that I was now a brother to a lovely little girl, something I’d always hoped for. The discovery of my new half-sister was a blessing in the midst of the storm. It was important that we protected her of course from the press furore my mother feared. Without the promise of anonymity, my mother chose not to give a statement to the police or get involved in the trial. It was a difficult choice for her, but I understood her fragility. The pressure and fear of its impact on her own family life was simply too much.

17.2) To top our reunion off I learnt that I was now a brother to a lovely little girl, something I’d always hoped for. The discovery of my new half-sister was a blessing in the midst of the storm. It was important that we protected her of course from the press furore my mother feared. Without the promise of anonymity, my mother chose not to give a statement to the police or get involved in the trial. It was a difficult choice for her, but I understood her fragility. The pressure and fear of its impact on her own family life was simply too much.

My father’s violent side

18) I revered my father. It was a relationship of respect but also one based on fear. I was scared of him and what he was capable of, as so many people were. It was a fear that had been instilled in me as a child through discipline, threats and punishment. It was his way of bringing me up and conditioning me with a set of principles and ideals that would set me in good stead for life. It isn’t fair to say I was unhappy as a child – I didn’t know any better – but I knew somehow we were different.

If things were done his way he was a charming man to be around, but everyone seemed to fall short of his expectations at some point and he would unleash fury and spite onto them. Like any son, I learnt to understand him, how to mediate with him and appeal to his nature. Patience, flexibility and an appreciation for his perspective were key to this. I learnt to value these qualities, to be sensitive and respectful of the individual. We simply cannot afford not to be. Life thrusts all kinds of people together, we have to understand tolerance if we are to get by at all.

If things were done his way he was a charming man to be around, but everyone seemed to fall short of his expectations at some point and he would unleash fury and spite onto them. Like any son, I learnt to understand him, how to mediate with him and appeal to his nature. Patience, flexibility and an appreciation for his perspective were key to this. I learnt to value these qualities, to be sensitive and respectful of the individual. We simply cannot afford not to be. Life thrusts all kinds of people together, we have to understand tolerance if we are to get by at all.

Ultimately, my upbringing made me who I am today and I can only be grateful for that. It was an environment where the incentive to achieve drove me to excel.

To most people, my father was simply misunderstood. They failed to relate to the traditions and cultural backdrop that underscored his way of doing things. His overreactions and sudden mood swings often took people by surprise. He was ‘unpredictable’ and it made him dangerous to anyone who didn’t know how to handle it.

I hear new stories about him all the time. I still don’t know what to make of this other side of my father’s life, but I remain a proud son regardless. Nothing anybody can say about him can detract from my love or devotion toward him. Understanding what drives someone to do things like this is part of loving someone.

When he lost it, he lost it. It didn’t matter where, and it didn’t matter who. Whether it was the bank clerk or a neighbour, the shop assistant or a kid – there was a confrontation. Threats, tirades of abuse, the whole works. Other than monetary motive, one of my fears is that – if my father was in fact killed – such a confrontation, typical as it was of my father, may have gotten out of hand. It is a hard pill to swallow but I have to face the facts and look at the realistic possibilities when I consider what may have led to my father’s death.

The last time I saw my father

19.1) It is a difficult day for me to talk about. By this point he had slowly cut off everyone who was ever important to him, and would erupt over the smallest of things. The hardest thing for me is that the last time I saw him he was shutting me out too. I never got the chance to make amends or patch things up. There remain the unsaid words of an unresolved standoff, a sense of incompleteness and that reconciliation has been stolen from us. It deepens the tragedy of all this. It is as if my father was on some self-destructive downward spiral and I just stood back and did nothing.

I’d moved back in, in 2007, after spending the previous years away at boarding school and a gap year. I wanted to look after dad and help around the house. I knew he had no-one else. A year later and rapidly deteriorating, dad was rushed to hospital for an operation to remove his diseased colon. I stayed at his bedside, praying for his recovery. In those few weeks we bonded more than we ever had in all the years before, but the operation – a colostomy – left him demoralised. I gave up everything to help him through and nurse him back to health, determined to see him regain his independence once more. At his most helpless I had helped him bathe, dress, eat, and use the toilet. This lasted for 6 months. It was heartbreaking to see him like this. Over time, I was able to retrain his strength and walking through supportive exercise. It was a struggle, but by the summer of 2009 he had fully recovered and was back to his old self.

When I saw dad on 15 October, I told him that I’d just had tea with the neighbours across the road. They’d been asking after him and wanted to know how he was. He was incredulous. I realised with dread that I should have ‘cleared it’ with him beforehand. As he flew into a wild rage he demanded that I recount every last detail of what had been said between us. It was a typical overreaction on his part. Our neighbours had always been a sensitive issue and now I’d gone out of my way to break his wall of privacy and divulge personal information. In his mind, I had gone behind his back in a way that was unforgivable and which in his pride he could not tolerate – it was the ultimate subterfuge.

I had been used to dad’s outbursts, but I thought we had got over this. I’d hoped he would have learnt to control his anger over this time, at least toward me. This was just days before my birthday. It spoilt our planned celebrations because he completely snubbed them after this and I remember the disappointment I felt. His temper was volcanic, I felt like I was a little kid in front of him again.

I had only been trying to help after all, to mediate between him and the neighbours. I felt like he owed me an apology, but knew he expected one from me first. ‘I wasn’t a kid anymore’ I told myself, I had a business to run, a degree to finish, a life to lead. I didn’t have time for these melodramatics. I chose to stand my ground and let him sulk it out. When he got like this with someone there was no telling how long it would last. He had to be given the time and space to get over it and cool down.

19.2) I regret ever being so stubborn. I should have made the first move, but I allowed myself to get caught up in my own life and work, to almost forget about home, waiting for that phone call from him, waiting for it to blow over – but it never did. It’s an impossible weight on my conscience. I should have been there for him, not blaming him for things. I was too naïve to realise what I was dealing with; too blind to see that his lack of contact wasn’t just his usual stubbornness but something far more sinister.

The longer I didn’t hear from him or see him, the more stubborn and hurt I felt, and the more I felt like he was pushing me away. I put off visits home and soon months had flown by. Like an idiot, I skirted and shrank away from the issue, still afraid of what he might say or do, too much of a coward to approach him myself and clear the air.

The longer I didn’t hear from him or see him, the more stubborn and hurt I felt, and the more I felt like he was pushing me away. I put off visits home and soon months had flown by. Like an idiot, I skirted and shrank away from the issue, still afraid of what he might say or do, too much of a coward to approach him myself and clear the air.

Often more was said between us through the unsaid – where actions spoke louder than words. These were things understood between us as a family, through years of habit. I made a few visits back to the house after October, hoping to open things up for reconciliation. I tried to carry on as normal. Little deeds were symbolic in themselves. I hoped if I did my bit, he would eventually reciprocate.

It was just the same old story to me. I had seen it all before: the same symptoms, the same inexplicability. It happened in cycles with dad. Only the summer before, his sister was supposed to visit us here in England. Dad had refused to return to Egypt for the past 40 years and having spent all that time apart it was to be a special reunion. Suddenly, my father refused to speak to her or the rest of the family, cutting them off completely. He took offence at something she had said and blew it out of proportion. He changed his email address, even his telephone number, and ignored her concerned letters. She couldn’t understand it. This silence went on for the next 6 months.

I wasn’t surprised my dad was blanking me, it was typical. I expected it all to blow over in its own time. He had done it to friends, colleagues, neighbours, my mother, and even family. This is one reason why I never felt worried, why I wasn’t concerned. This was the trap I allowed myself to fall into.

My father's disappearance: lessons learnt

20.1) When I spoke to some of our neighbours, they were concerned about dad because they hadn’t heard from him either. I didn’t take it seriously at all. If dad wasn’t speaking to me it was hardly surprising he had blown them off too. He’d already turned down their visits earlier. What they didn’t know of course was that they were indirectly the cause of our fall out in the first place. If dad was angry with me because I’d shared too much, I was hardly going to make the same ‘mistake’ again and upset him even further.

I was cynical at the time; they barely knew us after all. Over the 22 years we’d lived there we had never integrated or socialised with them, let alone shared or confided in them about our personal lives. Dad had drip fed them information over the years, and only what he wanted them to know. My mother and I were always told what to say and what not to say. This often meant we lied to the neighbours about things at dad’s behest. Ironically of course, this counted against me at trial.

I felt I knew better. This was a family issue. I wasn’t going to air our dirty laundry for the village gossip or rumour mill. I didn’t feel it was their business and there was no sense of permanence. It would resolve itself soon enough and everyone would carry on as normal. If only I’d been less dismissive. This complacency and fatalist stance that things would ‘work themselves out’ meant I didn’t confront anything or ask the right questions.

My biggest mistake was that I didn’t confide in anyone. I didn’t share my concerns or worries and this was my nemesis. I lacked the advice or plain common sense of a fresh pair of eyes; the mature outlook and experience of the neighbours. I was strolling along with the blinkers on, stubborn and stupid, careless and naïve.

20.2) Perhaps it is because I’ve spent my life compartmentalising things. I had to. It’s fair to say I had an unconventional childhood. From the age of 6, I was taught to adopt a string of new identities. I would be ‘Mark’ at home but ‘Andrew’ as soon as I walked out of the door. Of course, I didn’t know any better, dad made it seem like a game, but it meant that I never shared my home life with anyone. It was a separate world for me and I maintained its secrecy and privacy just the way I’d been taught to. Like my father, I didn’t share problems or concerns. I coped with difficulties on my own, adopting a ‘keep calm and carry on’ mantra. As I grew older, ‘home’ became almost peripheral. This isn’t easy to get across when you are in a courtroom and I had little by way of corroborating evidence at the time to contextualise my account. I think the jury really struggled to relate to this lifestyle – they had nothing to compare it to – and the prosecution were able to play on this to secure a conviction.

I know today that this lack of openness and sharing was fatal and I have put this relic of my past behind me. It was unfair on those I loved, unfair on my friends, and unfair on my loved ones. I’ve learnt so many important lessons, but in the hardest possible way – I have lost a father. I may be negligent, but I am no murderer.

Realisation and shame

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraphs 74 and 75]

21.1) The first real alarm bell for me that something was seriously wrong, had been a call from Social Services in February 2010. They were concerned my father might be missing. I was stunned. As far as I knew they were the ones supposed to be looking after him. It was their job to know where he was. Even though it wasn’t the first time, I had known my moving out wouldn’t be easy on dad – but he had assured me that everything was catered for and I shouldn’t worry about it. I had felt comfortable in the knowledge that he’d arranged private care for extra support while I was away. I allowed myself the complacency to immerse myself in London life and allow things to take their natural course.

If they had been looking after him all this time, why was this the first I’d heard from them? The last thing I imagined was dad being in harm’s way. Blanking me yes, in trouble no. I spent the next few hours trying to get hold of dad. I was sure there must have been some mistake. It wasn’t until the police turned up that I realised something serious was happening.

21.2) The notion that what had initially just seemed to be my father’s stubbornness was actually descending into a crisis, came like a cold sharp shock. What makes me feel so ashamed of myself today is that I had been blaming dad up to that point, believing he was up to his ‘old tricks’ again and not taking it all seriously. What really hurts, what really haunts me each day, is that I wasn’t there for him when he needed me most. It’s impossible to come to terms with.

21.2) The notion that what had initially just seemed to be my father’s stubbornness was actually descending into a crisis, came like a cold sharp shock. What makes me feel so ashamed of myself today is that I had been blaming dad up to that point, believing he was up to his ‘old tricks’ again and not taking it all seriously. What really hurts, what really haunts me each day, is that I wasn’t there for him when he needed me most. It’s impossible to come to terms with.

In the flurry of student life, in the rush of running a business and trying to make a name for myself and my own future, I‘d lost sight of and neglected the most important thing of all – my family. I failed as a son, and that pain, that regret, the ‘what ifs’, won’t go away.

Career and Paris

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraphs 78 to 82]

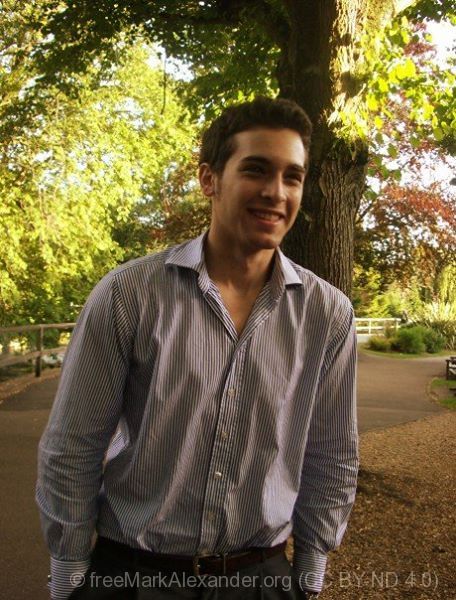

22.1) By the age of 21, I was running a successful freelance business while reading Law at King’s College London. I acted as a web consultant and software developer, involving myself with established businesses and vibrant start-up initiatives alike, both in London and internationally. I gave regular talks on innovation and business, and was passionate about my work. Trying to establish myself in the field was a constant thrill.

I was very fortunate to get a public school education at Rugby School on a prestigious ‘Arnold Foundation’ bursary (then in its inaugural year) and music scholarship. After gaining the highest mark in the UK for my ICT A Level, I was headhunted by IBM. It was an incredible experience and my work there resulted in my nomination for the national ‘Excellence in Computing Awards’ in 2007.

I had been volunteering at the Citizen’s Advice Bureau as an advisor in 2009 and made a point of giving back to the community through charitable initiatives like ‘Street Law’, a scheme set up to inspire local children in underprivileged schools to aim higher. We tried to spark their interest in university courses like the LLB through the talks and workshop events that we set up for them

My life had been blessed with opportunities and wonderful friends, I couldn’t have been happier. My father made all this happen. He was my greatest inspiration and mentor. He had made me, nurtured me, and steered me in the right direction. I was on the bright path that he had lit. I only wanted to make him proud of me, I’d never dream of harming him in any way. My father came first. This was my blood, my family. Our traditions hold these values highly. I had always prioritised him over everything, cared for him through thick and thin. This was my commitment.

To say I was ‘pushed’ by my father to do the things I have achieved would be to detract from the strength of my own ambitions. I think it’s important to remember that I’m highly driven in my own right. I believe you can only truly succeed if you have the passion within yourself to do so. A horse led to water is not compelled to drink. My father may have given my career the support it needed, but I saw myself as a self-made man.

22.2) When it came to deciding whether I would stay in London or go to Paris it was a choice that we made together. I had been looking forward to Paris more than anything; it was why I’d chosen to go to King’s College in the first place. I had fallen in love with the city and French culture. My girlfriend and I had prepared ourselves for the prospect of a long distance relationship. It was meant to be my big break, so any change of plan would be a big disappointment for me personally. Ultimately, we had a shared goal: dad always sought to best accommodate my performance academically. After much discussion over August we both realised that staying in London was the best solution.

Any suggestion by the prosecution that my dad somehow didn’t know what I was up to as I went to London to view apartments on 15th August, transferred the deposit to his account on 27th August, or packed my bags on 31st August is ridiculous. Yet, this was central to their idea of motive. It was all so far fetched that I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it.

The apartment we had found was a stone’s throw from university and our law library. It was ideal. Dad knew my girlfriend and I were in love, we had only just got back from a couple’s holiday together on July 26th. He was happy for us and moving in together was an obvious choice.

The concrete

[ref. ‘Case Synopsis’ – paragraphs 21 to 22]

23) What the police suggested to me on my arrest was so bizarre that I wrote it off as impossible, unthinkable. Revelations about my father’s body – attempted cremation and burial – sounded like something out of a mafia movie. The combined shock was numbing. This doesn’t happen in the real world.